The Trout Stream

- Oct 5, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 19, 2023

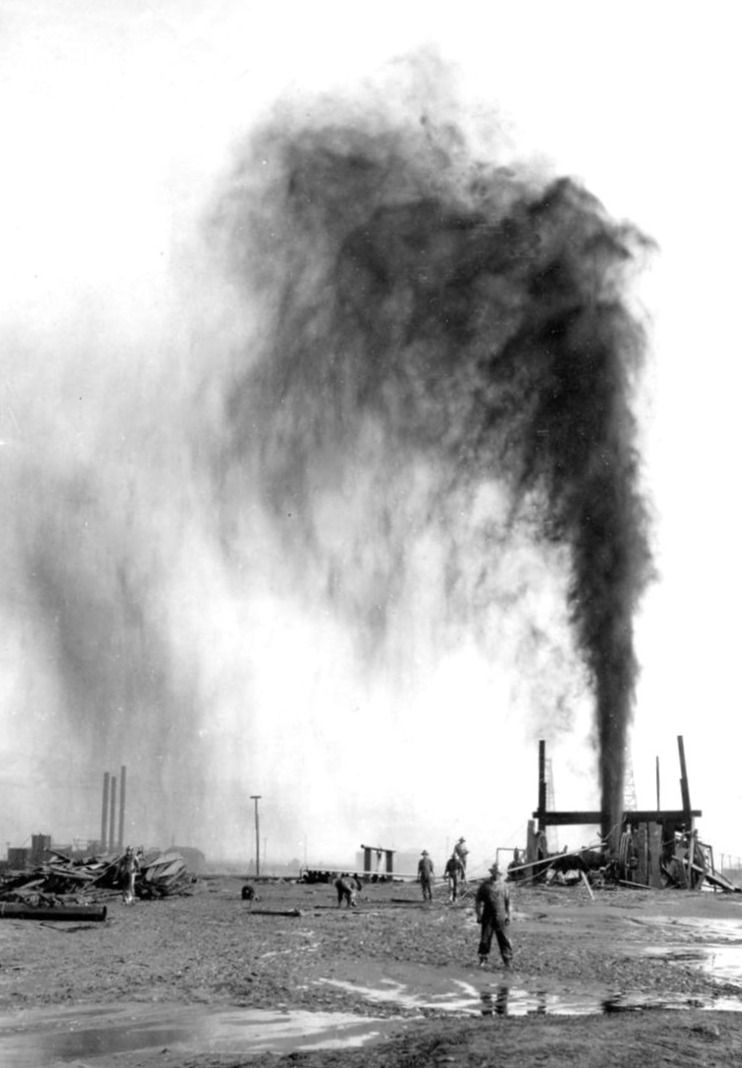

Lakeview Oil No. 1 Fried Well, Late March, 1910; Kern County, California

Below is a surveyed map of Kern County, California, S.W. of Bakersfield, dated 1910. The development of the Midway-Sunset Oil Field is underway, one of its principle players, Union Oil, later Unocal, later Chevron is predominate in this development. Vertical mine shafts were first drilled in the area in 1894 to very shallow Pliocene sands and heavy tar was hoisted out of the shafts by buckets. As the field matured deeper pays were found with cable tools and ultimately rotary rigs. The field would later go on to produce 3.2 billion barrels of oil, and counting (500 mm left recoverable), most of it from stacked Tremblor sands of Miocene age. Midway Sunset Field is the 3rd largest onshore oil field in the US.

Julius Fried, a grocer, and three other businessmen from Bakersfield, formed the Lakeview Oil Company in 1908 and leased land in the area halfway between Taft and Maricopa. Mr. Fried picked his new company's first well location based on a patch of red grass that grew in otherwise very dry sandy foothills of the Buena Vista Mountains. It was spud with great fanfare on New Years Day, 1909, each of the four principles in Lakeview Oil with a 25% interest in attendance.

The well was hard to drill because natural gas was often encountered in shallow, sandy beds requiring mudding up. That pesky gas slowed drilling progress and created a problem with setting a protective string of 8 inch casing inside 10 inch surface pipe. The Bakersfield boys were in over their heads, clearly.

The well came in with such force it pushed the 8 inch casing out of the hole 10 feet above the rig floor. By the time rig hands tried to close the full opening valve on the casing, it was already partially flow cut. The well was making so much formation sand it cut the rest of the valve out with an hour and surface control was totally lost. All hands abandoned ship.

Within a few weeks the well was estimated to be making 18,000 BPD of 18 gravity oil and so much blue gray sand it buried the entire rig floor, steam engines and even nearby the boilers. The derrick fell.

Earthen pits were dug down the hill with mules to capture the oil. As the well made less sand and cleaned up, flow rates increased to what was estimated to eventually be 124,000 BOPD. These rates were measured by the rate in which the pits filled up. The primary flow path for the oil down to this series of earthen, capture pits was an otherwise dry arroyo that became known as The Trout Stream.

There has been millions of words written about the "Lakeview Gusher" over the years and there are some amazing photographs of the well on the internet and in digital libraries all over California. The Fried well ultimately was estimated to have produced 9.5 MM BO over the year and a half it blew out of control. Less than half of that actually recovered and sold, mostly to the ever present "buzzard" of roadkill in the early California oil field, Standard.

When BP lost control of its Macondo well in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, the long forgotten Lakeview well was used an environmental catastrophe comparison and rightly named the worst onshore blowout in US history. I am not going to attempt to rewrite the good work already done on this Lakeview well throughout history; there is no need. It can be researched easily.

All well control events are noteworthy to me and because I have written about so many blowouts and fires over the past years I would be remiss to not at least mention this Lakeview event. As incredible as this blowout was it pales in comparison to others around the world and particularly the biggest of the big, the blowouts in the Golden Lane of Eastern Mexico in the early 1900's that I have written about extensively. 9.5 MM BO over 20 months is impressive but least us not forget the Cerro Azul well north of Tuxpan, Mexico that made 70,000,000 BO before it bridged off.

What is remarkable to me about this event, and others like it, as a blowout control hand myself, is the incredible ingenuity of the men who were forced to deal with some of these monsters. Had they ever seen that much bottom hole pressure before, the incredible force of 100,000 BPD flow rates? Did they fully understand the benefit of mud weight? For the most part they were drilling Mother Earth with cable tools when She was raging with bottom hole pressure. They had no idea what to expect and no blowout preventers to protect themselves.

I was taught well control by David Thompson, and Martin Kelly; them by Boots Hansen and Coots Matthews, them by Red, and Myron. Were roughnecks and drillers in the early 1900's able to draw on years of experience in controlling wells like Lakeview well?

No. They winged it. And often in incredible ways. No two blowout events are the same, ever. Anywhere. To control them one must be the ultimate problem solver.

On the right, six months after the initial loss of surface control, the well was still making lots of sand but confined to flow up the protective 8 inch OD casing string. The ground around the well was still solid enough to recreate a partial derrick to support the construction of a cofferdam around the casing in hope that this would help cause enough formation sand to build up over the casing to shut off the flow. It was a rather feeble attempt to begin building hydrostatic pressure against BHP. The cofferdam was built in hopes of choking the well back.

The 'box" helped contain the flow and direct it down the "Trout Stream" to pits where the oil could be pumped into storage tanks.

Within months of the completion of the cofferdam, sufficient hydrostatic back pressure against the fragile, low frac gradient sand at 2,250 feet caused the blowout flow to finally breach the 8 inch casing shoe, then the 10 inch casing shoe, and the well began to crater. The crater swallowed the entire box, cofferdam assembly. One day it was there, two days later it was gone.

A massive undertaking then occurred involving sand bagging the crater to confine the oil flow and send it down to earthen pits. Hundreds of men worked non-stop; feed sacks were filled with the same formation sand the made for the first four months it was out of control.

The crater would collapse and cause the circular sandbag dam to have to be rebuilt. By December 1910, a well nearby called the "Tight Wad" No. 3 blew out and caught fire on top of a hill; the fire created enough light that men could work around the clock sandbagging the Lakeview well, four miles away.

Both the cofferdam and sand bagging helped achieve a more accurate means of gauging flow rates. The Trout Stream was damned up and flow was diverted down hand dug ditches where liquids could be measured. For over a year the Lakeview well produced 45,000 BOPD with little decline.

Union sold most of this oil for 30 cent a barrel, to the buzzards, and it was almost sufficient to cover the cost of lawsuits and claims made against the company. The original four Lakeview owners were taken completely out of the mess and went back to selling groceries.

And, just like that, on June 9, 1911, 544 days after the well turned loose, the bailer sailing high into the California sky, the crater hole sloughed, bridged off and within hours completely stopped flowing, dead as a door knob.

Union Oil pumped out the crater out and excavated dirt to expose the actual well bore containing the 8 inch casing, seen on the left. A makeshift deck was built out over the crater, a gin pole erected over the original hole and the well bailed out to within 10 feet of its original TD.

The crater was filled in, a tie back was done to bring the casing back to ground level and a wellhead installed. The well flowed 30 BOPD up the 8 inch for several years. It was abandoned in 1918.

The Lakeview Well was offset five different times over subsequent years, on all headings on an imaginary compass, and oil was never found in the 2,225 foot sand. It is believed the sand that produced over 9.5 MM BO was only 70 feet wide but over a mile and half long, traversing down dip, basinward, into a nearby syncline that super charged the sand lense hydraulically and provided the over- pressure.

This theory was tested later by geological mapping and volumetric estimates of original oil in place were done in such a way as to suggest the total recovery of original oil in place with the 2,225 foot sand lense was upwards of 80%. That one well drained the entire sand. It was, as Charlie "Dry Hole" Woods often said later, a goddamn fluke of nature.

Flukes of nature are what oil men live for. And it is what well control experts, since Alexander Ford, Karl Kinley, Pat Patton, Red Adair, Boots Hansen, Coots Matthews, Joe Bowden and B.J. Cudd... sort of hung around the office all the time, waiting for. To get the call to come fix flukes of nature.

The monument above marks the well location of the Lakeview well and is easily found today just north of Maricopa, off Petroleum Road. There are old railroad ties and heavy timbers embedded in hard soil nearby, likely remnants of the old cofferdam built around the well. The crater is visible and all of the nearby soil dense, like asphalt, from the 4 MM BO that was never recovered from the blowout and that soaked into the ground.

I've been there. Places like this cause you to sit on a rock for hours and imagine what it was like 120 years ago to have been involved in the event and to take stock in the nature of the men who worked on the well.

The history of worldwide oil and gas industry is truly a remarkable thing.

Comments